The Algorithm Has No Taste (or, The Death of Weirdness)

What happens to art, imagination, and surprise when the algorithm decides what’s worth seeing?

There was a time when weirdness made culture move forward. I was 20 years old, and was handed a beat-up copy of House of Leaves by my coworker while working a summer job at the Billabong/Element store in Times Square. I was told, “It’s so weird, you have to read it,” and that was enough for me.

We used to seek out ‘weird.’ I’m talking about the kind of weird that didn’t test well, didn’t chart, didn’t slot neatly into a genre, and instead created new ones. The kind that gets shared from person to person, group to group, and culture to culture in “have you seen this?” emails or shared music at an after-party. The kind that initially confused people, and then enchanted them, leaving them unable to resist sharing their experience.

Now, everything is coherent by design- coherence meaning the algorithmic sameness that keeps us watching. Every song is an interpolation of another hit, every movie a remake of the same intellectual property, every face optimized for palatability. It’s not that taste disappeared; it’s that we handed it over to the algorithm, and the algorithm doesn’t actually have any. Taste shapes what gets remembered, what gets funded, and what fades away.

This isn’t just about losing odd art; it’s about what happens to imagination, politics, and possibility when the systems that feed us decide what’s palatable.

The Tension Between Taste and Consumption

We talk about “consuming content” the same way we talk about eating fast food: it’s cheap, constant, and engineered to hit the same pleasure points every time. Taste used to be about discernment, about risk and discovery. Now it’s a performance metric. To be “in good taste” online just means being aligned with whatever the feed already favors. We’ve traded curiosity for coherence, and it shows.

When people are bemoaning the ever-rising cost of groceries, crowdfunding to feed their families, and fundraising to pay for kids’ lunches at schools, we can always feast on content. Our instinctive, reflexive, biological imperative to nourish ourselves, one way or another, is evident in the language that we use. Forget the cake, let them eat short-form videos. We binge, snack, scroll the feed, devour hot takes, and reheat old nachos. We let her cook, we say “she ate”, we call a post “juicy,” and the tea deliciously messy. Our metaphors betray us: we’re starving for connection (and often, literally food), but we keep feeding the machine.

Art hasn’t always meant entertainment, but now it’s all collapsed into content. Content, unlike art, must be, if not fun, at least inoffensively engaging enough to keep us scrolling. We lost weird art. Weirdness used to be allowed to linger, to confuse, to provoke. Now, media that can’t be clipped, captioned, or explained in thirty seconds gets quietly discarded as irrelevant. Scroll through TikTok and you’ll see how quickly creative expression collapses into templates: the same “clean girl” aesthetic, the same color palettes, the same unboxing angles, the same abstract blobs on every book cover. What’s marketed as personal taste is really platform fluency, and it doesn’t stop at the screen. The same optimization logic bled into our bodies: the pursuit of “Instagram face,” achieved through fillers, veneers, and filtered symmetry. It’s the algorithm made flesh, beauty engineered for the feed.

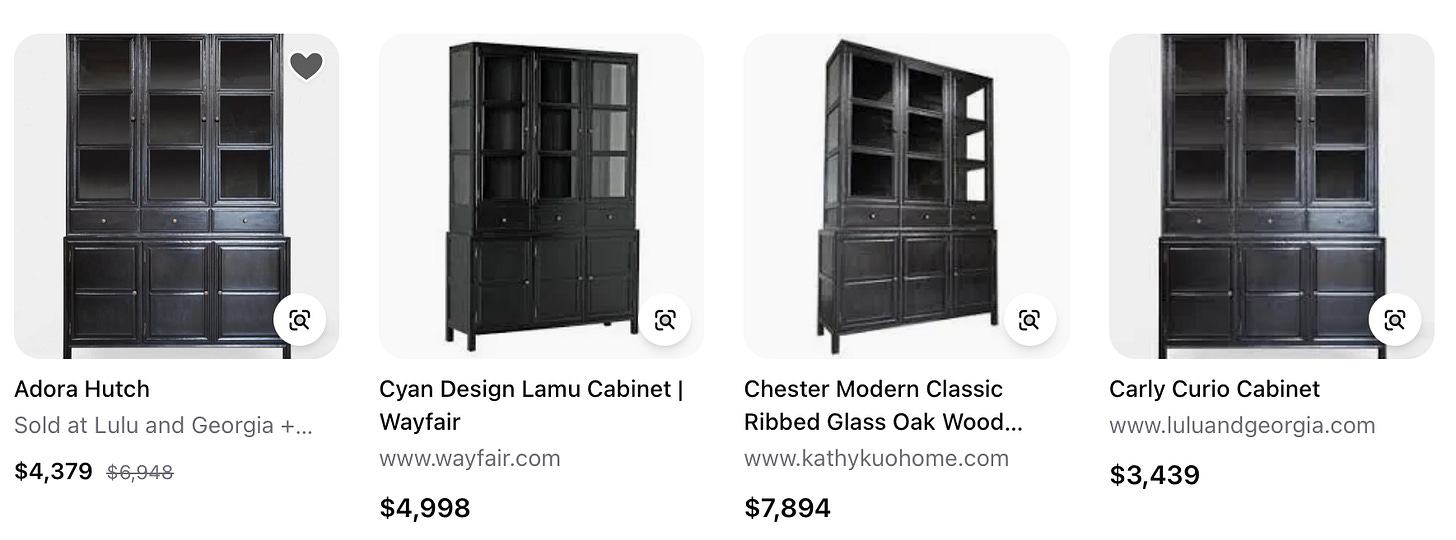

What looks like infinite choice is often just duplication at scale. Sometimes it’s literal, the identical white labeled cabinet rebranded by five retailers, the same dropshipped sweater marked up for a new audience. The illusion of abundance hides how narrow our actual choices are.

We don’t just consume content anymore; we perform our consumption. For every song released, there’s a flurry of “reaction” videos. The “taste” we signal online is less about what moves us and more about what moves numbers. Aesthetic alignment has become a kind of social currency. It’s a feedback loop; our tastes teach the algorithm how to please us, and the algorithm teaches us what to want.

Considering aesthetic taste and tastemakers can seem like a trivial concern when it feels like society itself is teetering, but art matters. It always has. Art provokes, inspires, and mirrors us. What we elevate shapes how we think and what we believe is possible. Researcher Yağmur Özbay at the University of Amsterdam found that art helps people engage with complex or uncomfortable social issues, a reminder that creative discomfort is how societies evolve.”

Shared taste has also always been a kind of social glue. Within geographic communities, we bond around sports teams, local bands, or the foods that define a place. Taste shows us where we belong, who we stand with, and who feels like an outsider. Losing the ability to define or expand that shared sense of taste doesn’t just make culture duller; it makes belonging harder to find.

Philosophers, dating back to Plato, have considered the concept of aesthetic taste. David Hume said beauty lies in the mind, not the object, that our sense of the beautiful shifts with culture. Karl Marx pointed out that “the ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas.” The same is true of taste: those who shape it hold power. The question, then, isn’t just what do we find beautiful? It’s who gets to decide the options.

The Death of Weirdness

The big problem with weirdness is that it doesn’t scale. And realistically, most of it doesn’t work. It’s a numbers game that requires a lot of attempts to find something that breaks through. And in an economy where engagement equals money, reliable scalability is the only thing that matters.

Once upon a time, we had strange, unruly art projects that didn’t seek approval, because there was no algorithm to impress. Go back and ask Gen Xers about college radio stations, local record stores, or independent zines: weird thrived there. As any elder millennial can tell you, the early internet was a lawless place. We had Salad Fingers, Ebaum’s World chaos, and all manner of bizarre Flash experiments, the kind of cultural lore that felt alive precisely because it wasn’t optimized for anyone. Those corners of the web were messy, participatory, unmonetized, and full of risk.

Blogs, forums, and early YouTube channels made taste feel communal again in an exchange, not a transaction. But as platforms matured and insisted on profitability, curiosity gave way to optimization. Now, the same logic that once connected people has been repurposed to police taste. The algorithm’s goal is coherence, to keep you watching, scrolling, and buying, and weirdness breaks that coherence.

Where weirdness once drove cultural evolution, forced coherence has created cultural inbreeding, continually narrowing our tolerance for what feels strange. Even when we do get a burst of whimsy, like Meg Stalter being delightfully unhinged on press tours or the Las Culturistas Culture Awards testing the limits of theater-kid absurdity, it reminds us how hungry we are for something unpredictable. But the machine still finds a way to smooth it out, to package it as measurable content that serves the algorithm. Even weirdness has a content strategy now.

Even theatrical revivals now come pre-optimized for the feed. Nicole Scherzinger’s Sunset Boulevard turned the title song scene into a live street sequence filmed in real time, a breathtaking setpiece that also doubled as perfect viral content. Every night, crowds filled the block around the St. James Theatre to capture it, their phones raised as lights and cameras swirled around the action. Rachel Zegler’s turn in Evita at the London Palladium offered a similar kind of engineered transcendence: the balcony scene staged like a ritual for social media, designed to be filmed again and again.

These moments are both beautiful and disorienting, historic, inventive, and deeply modern, but we can’t pretend they weren’t also built for the algorithm. TikTok is flooded nightly with footage of fans performing their presence, recording not just the show but themselves watching it. The experience became inseparable from its documentation.

Even Jennifer Lopez, one of the few artists rich enough to experiment, made a film, This is Me…Now, that was gloriously, ambitiously weird, and she was ridiculed for it. She has $400 million. Let her make weird stuff. More millionaires should exclusively be using their money to fund nonconformist, strange, potentially bad, weird stuff. Lord knows there’s enough financing for more “sameness.”

Weirdness used to shape the future- Frida Kahlo’s surrealism, David Lynch’s nightmares, Peter Gabriel’s musical experimentation, and cult films like The Big Lebowski and Rocky Horror Picture Show all stretched taste until it tore. Now, our media continues to breed within an ever-narrowing family tree, culture cannibalizing its own potential. Without embracing weirdness, would we have ever gotten Groundhog Day (and then Palm Springs, Russian Doll, Looper) or This is… Spinal Tap (and then Best In Show, What We Do in the Shadows, and The Office)?

Weirdness didn’t just fade; it was edited out. Somewhere between art and algorithm, risk gave way to reassurance. The same systems that once helped us find what we loved now decide what’s worth loving at all. To understand how weirdness disappeared, we have to look at who used to decide what we saw, and who decides now.

Gatekeeping: From Tastemakers to Algorithms

It wasn’t always this way. Once, there were patrons of the arts, editors, critics, small magazines, record labels, and independent radio DJs selecting what art was seen, heard, and discussed. They were the human bottlenecks of taste. Yes, it was flawed and too often exclusive, giving unearned privilege and access to well-connected individuals, but there was always a chance to find your stage. You could trace a lineage from a magazine editor’s obsession to a subculture’s identity. A punk zine might spark a local scene. A critic’s review could launch an entirelty new genre.

The internet promised to blow that open. Anyone could make something; anyone could be found. And for a while, it was true, and more and more content was created, shared, and circulated. As is inevitable under capitalism, profit shifted to the top of the hierarchy of needs and ultimately became the only thing that mattered. This was framed as a tech problem and therefore demanded a tech solution. Now, the tastemaker is an algorithm, simultaneously invisible and unaccountable. Whether we have five choices or five thousand, we can only choose from what we know exists.

The main limitation of technology and algorithms is that they can only replicate the past. They cannot create something new. Even AI and large-language models only learn the statistical relationships between words and phrases, and then repeat them. They do not develop new relationships or ideas if they’re statistically unlikely. This technology rewards sameness and punishes risk. Serendipity, once an established method of discovery, has been replaced by prediction. What we call personalization is really just standardization with more specific coding and better branding.

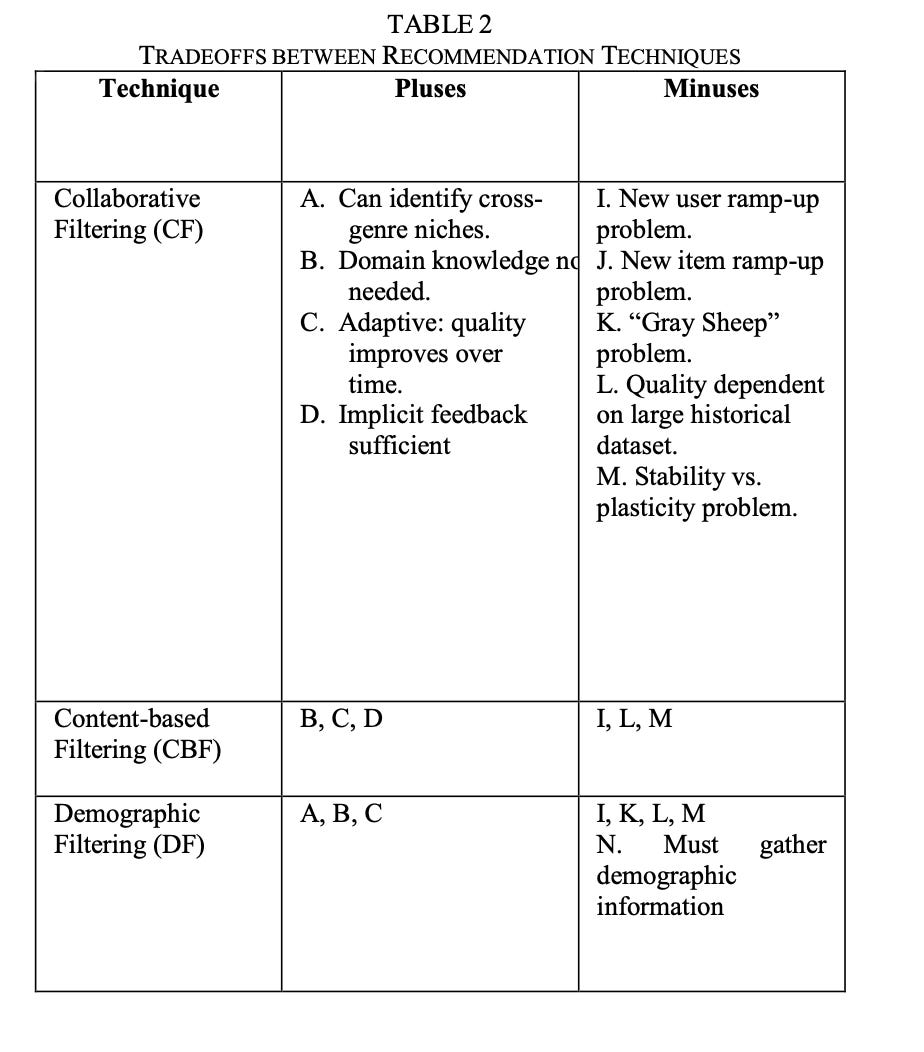

“The algorithm” online is really a patchwork of different filtering systems- recommender engines, social-information filters, reference networks, and content-based models, each with its own weak spots. None of them are neutral, and none of them knows everything. Each learns from what’s already been popular or who you’re connected to, and each rewards predictability.

Content-based filtering can only show you more of what you already like; social filtering values sameness, rewarding what your circle already prefers.” But if there’s nothing new under the sun, it’s doubly true under a filtering system. “Algorithms are limiting the future to the past,” as digital philosopher Jaron Lanier said. What might once have been an engine of discovery has become an instrument of repetition, an echo chamber disguised as personalization.

Technically, what we call the social-media “algorithm” isn’t actually an algorithm. In mathematics, an algorithm “remains in its essence an equation: a method to arrive at a desired conclusion,” as Kyle Chayka notes in Filterworld. To be more precise, the formulas that shape our content are heuristics, a set of guesses designed to approximate what might keep you engaged. There’s no single right answer, only probability weighted by past behavior and commercial incentive. But while the term isn’t technically accurate, its cultural meaning holds: what we call the algorithm is shorthand for the opaque logic that now governs discovery.

Yes, when online content is being generated at the pace it currently is, we need a management system to keep the internet useful and functional. On YouTube alone, over 720,000 hours (or 82.2 years) of video are uploaded every single day. We need a way to filter this overwhelming world of content, but the filters we got are trained on the logic of profit and not a taste for weirdness.

Chayka notes that “the popular becomes more popular, and the obscure becomes even less visible,” urging conformity. We can’t always identify the magic combination of features that made something obscure, delightful, and important, so it can’t be measured. Serendipity and surprise have no data history to reference, so they disappear. The problem becomes that the algorithm doesn’t just decide what we see anymore; it decides what gets made. When funding and platforms follow easy engagement, artists, writers, and creators are forced to start designing for the feed, reverse-engineering their work to match what the machine has proven people already like.

Algorithms aren’t independent entities, no matter how much we talk about them that way. “The algorithm” is shorthand for a company’s choices. As Tufts University sociologist Nick Seaver told Chayka, “The algorithm is metonymic for companies as a whole. The Facebook algorithm doesn’t exist; Facebook exists.” TikTok without its eerily prescient algorithm wouldn’t be TikTok at all (which fed into creator anxiety around the ByteDance deal).

When executives outsourced the task of tastemaking to code, they didn’t remove human bias; they mechanized it. Algorithms are equations shaped by human inputs and commercial decisions. Every ranking, every recommendation, every “For You” page is a human value judgment written in code. The problem isn’t that technology is making taste decisions for us; it’s that the people who build and profit from that technology already decided what those tastes should be. When white-supremacy culture goes into the machine, white-supremacy culture comes out. The same goes for patriarchy and capitalist extraction. You can see it in the quiet reversal of body-positivity and neutrality that once felt revolutionary and inevitable online, which has once again been replaced by the same old demands of thinness, whiteness, and filtered femininity. We learned to optimize ourselves long before the machines took over the job.

Our traditional cultural tastemakers were social curators of aesthetics, art, and design, but the new algorithmic editor doesn’t curate; it conditions. It teaches us what to want, and then congratulates us for wanting it. Weirdness, by definition, can’t survive that process. It doesn’t fit the data set. To appease shareholders, platforms optimize for engagement, not art. The flattening of taste mirrors the ruling ideas of this epoch that financed and built these systems: whiteness coded as default, patriarchy disguised as “neutral,” and creativity mined for profit.

Even when the algorithm works in a way that seems to serve us, we need to remember these systems aren’t neutral curators; they’re mechanisms built to serve commercial outcomes. Every creative risk that gets punished for low performance is another reminder that our feeds were never designed to make the best idea rise, they were designed to maximize profit. When creativity is conditioned by systems designed to reward conformity, art loses its ability to challenge power.

Who Benefits When Weirdness Dies

Weirdness isn’t just aesthetic; it’s democratic. It’s how new ideas enter the world, and how we learn to find echoes of history for the future. When we train ourselves to fear confusion or discomfort, we train ourselves to accept authority without interrogating it. Scholars who study fascist systems of control have long noted that small acts of resistance, questioning authority, embracing difference, and refusing to conform are how people build the muscle to push back against power.

But the algorithm doesn’t reward that kind of resistance. It rewards coherence. It rewards compliance. Every “For You” page is a quiet lesson in obedience disguised as preference. Every time the feed flattens a new idea into content, culture loses something vital. Weirdness is the oxygen of creativity, the unmeasured, unpredictable spark that keeps culture evolving. Without it, everything starts tasting the same.

The feed might have trained us to crave sameness, but it can’t erase the human impulse toward strangeness. Weirdness isn’t dead; it’s just off-platform. It lives in the group chat, the basement show, the tiny Substack no one’s quoting yet. The algorithm can flatten taste, but it can’t kill curiosity, not completely. The next wave of culture won’t be optimized. It’ll be weird again, because weirdness always finds a way to survive.