We’ve Been Trained to Crave

How the Internet Rewired Our Appetites and Replaced Curiosity with Comfort

I’d love to introduce you to my local barista, Emily. The first thing to know is that Emily is an angel, one who knows my daily coffee order, and she begins putting in my large, skim, sugar-free hazelnut latte as soon as she sees me open the café door. I imagine her brain as a giant, brilliant database of drink recipes, regular customers, timetables, and orders. In other words, Emily is a human supercomputer who uses gathered data to give me (and probably countless other customers) exactly what I want, streamlining the process of getting my coffee, heading back out the door, and carrying on with my day.

What looks like efficiency in Emily is really memory, attention, and small-scale empathy, incredibly human things that no algorithm can replicate. The algorithm imitates that relationship, but it’s transactional. It doesn’t learn in order to better serve; it learns so it can condition. Companies have engineered systems that replace our natural, human appetite for curiosity with one for compulsion. Rather than engaging in critical thinking and discernment, we settle for ease and optimization. Every post, clip, and trend is designed to bait us, then go down easy, leaving us wanting more. The internet has turned cultural appetite into a matter of biohacking for the sake of manipulation, and the result is a population in a state of insatiable consumption.

The Body Learns the Feed

We say we consume content, not savor it. Our media diets are fast, frictionless, and endlessly refilling, autoplaying into the next bite. Last time, I wrote about how our language around taste (bingeing, sipping tea, eating and leaving no crumbs) reveals how we feed the content machine. It isn’t just a metaphor; it’s biological.

Our attention systems run on the same reward cycles that govern hunger and craving. Dopamine, the brain’s chemical messenger for motivation and anticipation, doesn’t make us feel joy so much as it drives us to look for it. It fires not when we get the reward, but when we expect that something rewarding might happen. Every scroll, like, and notification teaches our brains to anticipate a tiny hit of novelty or social affirmation, and it feels good. Because the rewards are unpredictable, the brain keeps checking for them, exactly the way we check the fridge every few minutes when we’re feeling a little snacky, on the chance something new might have appeared. Since it’s the expectation that gets it flowing, it’s an easy system to engineer around. When a company, casino, or social media platform is engineering for maximum profitability over human benefit, it’s also an easy system to abuse.

That uncertainty is exactly what the system was built to exploit. Stanford psychiatrist Anna Lembke, author of Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence, explains

“Feel-good substances and behaviors increase dopamine release in the brain’s reward pathways. The brain responds to this increase by decreasing dopamine transmission—not just back down to its natural baseline rate, but below that baseline.”

Repeated exposure creates a dopamine deficit state, where we become less able to experience pleasure and more dependent on quick fixes. The logic is simple and cruel: the more we scroll, the duller real life feels, which makes us want to scroll more.

As Lembke told Stanford Medicine News,

“Social connection has become druggified by social-media apps, making us vulnerable to compulsive overconsumption. These apps release large amounts of dopamine all at once, just like heroin, meth, or alcohol.”

Behavioral neuroscientists Luke Clark and Martin Zack call these “engineered highs.” The added infinite-scroll and autoplay mechanisms on digital platforms mimic the same reinforcement schedules we find in gambling.

“By enabling near limitless diversity and speed of delivery of non-drug rewards, digital technology has permitted engineering of reinforcers with addictive potential that, delivered under natural conditions, would likely never become addictive.” Engineered highs: Reward variability and frequency as potential prerequisites of behavioural addiction.

Unlike casinos, which are legally required to limit how far they can exploit human impulse, digital platforms face no such oversight. The same reinforcement patterns that keep gamblers pulling the lever now live in our pockets, disguised as feeds and notifications. Each swipe is another spin, another maybe this time. There is no dealer to cut you off, no closing bell, no moment to cash out. The algorithms behind them are our appetite trainers, teaching us to crave what keeps them profitable, and because attention is the currency, there’s no incentive to let us stop playing.

Algorithmic Anxiety and Appetite Engineering

If the first half of this is biology, the second is belief. Once you know your experience is being shaped by an invisible system, it’s almost impossible not to start negotiating with it. That’s algorithmic anxiety, a term coined by Rutgers professor Shagun Jhaver. The concept emerged from a study of Airbnb hosts, who described a kind of double negotiation, or a way of performing both for human guests and for the platform’s inscrutable algorithmic evaluation. That uncertainty, researchers found, breeds a constant tension: the sense of being judged by something you can’t fully see or satisfy.

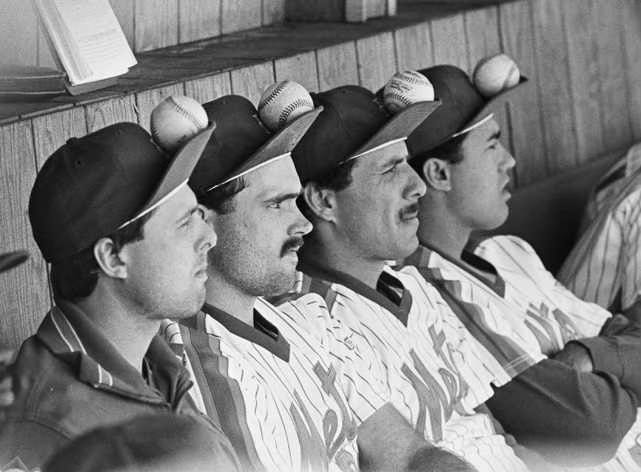

For creators, that awareness feels like superstition. You post at the “right” hour, use the “right” trending sound, and caption in the “right” tone. You might not believe in magic, but when your team is down, you’ll still flip your baseball hat inside out and pray the rally-cap superstition holds true. The rituals create a fleeting sense of control in a system designed to withhold it. The cycle repeats: anxiety seeks comfort via ritual. That ritual leads to temporary relief, which also leads to renewed dependence. It’s operant conditioning disguised as content strategy.

We can laugh at how silly it all is, but we can’t write it off as delusion. Social platforms design these beliefs by deliberately hiding their formulas while rewarding the behaviors that sustain them. As media scholar Taina Bucher writes in If... Then: Algorithmic Power and Politics, most users don’t know exactly how these systems work, but they sense that something unseen is shaping what they see. That uncertainty breeds a mix of frustration and fascination, the kind that makes people start guessing at the rules, tweaking their behavior, and policing themselves in hopes of staying visible. People end up doing the work of optimization, trying to reverse-engineer the rules through old wives’ tales, rumors, and endless trial and error.

The power imbalance is enormous: users generate the content, but the platform sets the terms. Even rumors of “shadowbans” or “dead accounts” keep creators chasing the next hit of visibility. Björn Lindström, professor and lead researcher at the Mechanisms of Social Behavior Lab, found in a 2021 paper that “human behavior on social media conforms qualitatively and quantitatively to the principles of reward learning.” We’re not addicted to the content itself, but to the process of guessing what the system wants and testing if we got it right this time.

Christian Sandvig, professor at the School of Information at the University of Michigan, calls this corrupt personalization, the process by which our choices and preferences are algorithmically reshaped. “Over time,” he writes, “if people are offered things that are not aligned with their interests often enough, they can be taught what to want.” In other words, the machine doesn’t just predict preference the way Emily the Barista might; it creates it.

Don’t believe me? Ask the Labubus hanging from the backpacks in my front hallway. Yes, the same ones I rolled my eyes at a year ago and swore I’d never give in to. Eventually, after seeing them in literally thousands of posts, they started to change. Maybe they were kind of cute. They’re fun, right? Harmless, even. How could anyone begrudge you a moment of frivolity in a hellscape of a world? And now here they are, the plastic embodiment of an engineered desire, the consumerist expression of micro-trending whimsy.

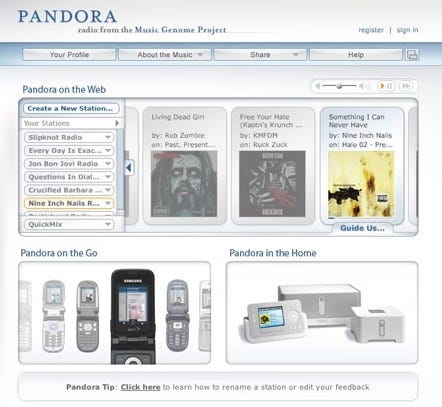

Long before the “For You Page,” Pandora was already narrowing the playlist. I eagerly signed up for a free, ad-supported account, but no matter which songs I started with or which ones I thumbs-ed up or down, every station I created somehow turned into Coldplay. Maybe it was just 2008, but it was also a primitive version of the same logic: convergence through repetition.

Pandora was one of the first algorithmic music platforms, built on its proprietary “Music Genome Project,” which claimed to personalize listening by identifying shared traits between songs you already liked. In reality, the longer a listener plays, the smaller the range becomes. What begins as appeasement (“I’ll post what the algorithm likes”) becomes genuine appetite (“I like posting this kind of thing”).

Algorithmic anxiety changes what we do, and it also changes why we do it. We start to internalize the machine’s logic of reward and punishment until the act of creation feels inseparable from the fear of invisibility. When that happens, curiosity flattens into compliance. Pleasure becomes performance. And art, which once thrived on risk, subverted expectations, and surprise, begins to resemble the machine that feeds it.

So much of this conditioning depends on familiarity and our preference for the recognizable over the new. The next trick of the algorithm is how it teaches us what feels safe.

Familiarity and Neural Pathways

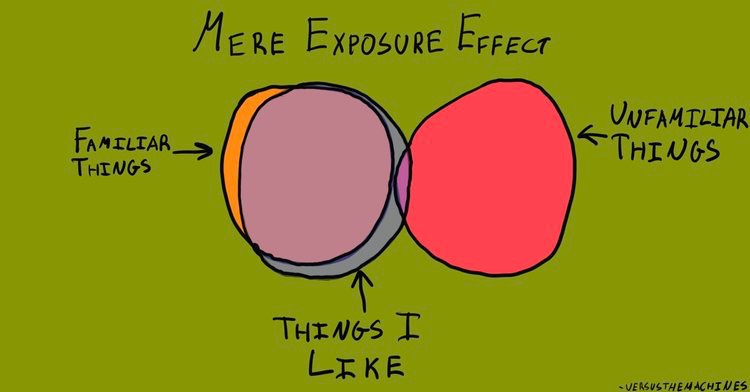

The human brain is built to recognize patterns; it rewards itself for finding them. We like what we know because knowing feels safe. Psychologists call this the mere-exposure effect, or the familiarity principle: the more we encounter something, the more we tend to like it. Novelty demands mental energy. We have to create new neural pathways, new comparisons, new context, and the algorithm knows most of us are too tired to do that work.

Neuroscientists have long observed that it takes multiple exposures to new music before listeners develop real affinity for it. Studies in music cognition show that the “sweet spot” for musical enjoyment sits between surprise and recognition, the moment our expectations are challenged but still met. Research by Robert Zajonc, who first described the mere-exposure effect in 1968, found that “repeated exposure of an individual to a stimulus is a sufficient condition for the enhancement of his attitude toward it.” In other words, familiarity breeds liking.

But on today’s platforms, the window for that exposure has almost closed. Depending on which study you read, the average watch time before a viewer swipes away is somewhere between three and ten seconds. Creators are coached to hook audiences in the very first frames and words, because that’s all the time the algorithm gives them. If we are talking about music, that means the moment a song feels unfamiliar, the listener is gone long before the chorus. Three seconds isn’t long enough for the brain to build those new neural pathways or for curiosity to turn into taste. The repetition training doesn’t happen here, because the unfamiliar is buried in favor of the already familiar. What’s popular continues to rise to the top, not because it’s any better, but because it is faster to recognize.

That is why a new song rarely hits on the first listen. Our brains need a few rounds to recognize the structure, to learn when the chord will resolve or the chorus will return. In a healthy system, that is how curiosity becomes taste. But in the algorithmic system, the feed doesn’t wait. It reads hesitation as disinterest and instantly serves something safer. The slow process of learning to like something is treated as a failure.

You can see this logic play out in how streaming platforms tailor experiences down to the pixel. As many parents or caretakers know, when the day comes that you use your Netflix or Spotify profile to play kid-friendly content, the algorithm starts adjusting your recommendations, assuming you too love Bluey or Princess Singalongs. Netflix changes its cover art depending on who is watching: the same show might feature different actors, moods, or colors based on what the system thinks you will click. If you have seen any of the “Group 7” discourse on TikTok recently (which is a whole topic for another deep dive), Netflix even added a “Group 7 Only” section on its homepage for some algorithmically selected users. These personalization cues are subtle, but they’re designed to feel familiar, understood, and safe, collapsing friction to make you more likely to keep watching. In machine logic, difference reads as error.

The same mechanism that trains the brain to anticipate dopamine also trains it to avoid uncertainty. The algorithm simply weaponizes that impulse, translating the familiar into engagement and the new into risk. As Filterworld author Kyle Chayka puts it, algorithmic normalization finds what fits in the “zone of averageness.” That zone keeps narrowing. Novelty now feels unsafe; comfort feels good, right, and moral. The result is a cultural loop where art, ideas, and identities converge toward what is most legible to the feed. The weird, the long, the slow burns, the things that require time to unfold, all get edited out.

Our brains were not built for infinite choice. They were built for curiosity bounded by context, for moments of wonder that emerge from boredom. When the algorithm collapses that space, we lose not just attention but the capacity for awe.

Learning to Taste Again

If the algorithm taught us to demand ease, the way out is to spend time with friction and discomfort. Reclaiming our innate appetites means putting forth the kind of effort that makes pleasure feel earned and real.

The resurgence of collecting, of owning tangible things like records, books, zines, and film cameras isn’t only about nostalgia. It’s a way back to how intentionally engaging with art and creativity feels. Streaming offers everything, but gives users nothing to hold on to. A film can vanish from the internet overnight. The playlist we curate might live on a server, but it never really belongs to us. Physical art asks something of us in return: care, space, and time. And we must acknowledge that there’s also a financial investment that is inaccessible to everyone. A vinyl record demands that you choose a side, drop the needle, and stay through the end.

Reclaiming ownership is also about slowing down to reclaim tempo on our own terms. Friction makes discernment possible. It forces us to decide what’s worth our attention. Recent reports reveal that TikTok users might build compulsions and scrolling habits in the course of flipping through 260 videos in a 35-minute session. Digital culture treats delay as a flaw, but slowness is how we absorb experience. Philosopher Byung-Chul Han writes that modern life erases contemplation, trading depth for constant activity. The feed depends on speed because thinking slows it down.

Counter-practice doesn’t have to look radical. It can live in small rituals:

Listen to one album, start to finish, without multitasking.

Watch a movie or a show without a second screen in hand.

Keep a running list of “one weird thing a week,” something that stays in your head for reasons you can’t explain.

Read something offline, then talk about it with a real-life person instead of posting about it (or at least before posting about it.)

These simple acts reset appetite. They remind the brain that satisfaction grows not through velocity of exposure, but in staying with what you love long enough to notice its texture. Curiosity builds culture. When we make room for friction, maybe even intentionally seek it out, curiosity has space to return. In a world obsessed with optimization, savoring becomes a quiet act of defiance. The algorithm has learned how to feed us. The question is whether we can learn to taste again.

It's funny you write this, I just heard a not-so-fun-fact that streaming is way more resource intensive than vinyl or CDs. I just did a little search, this popped up first but there's loads of data out there... so from an environmental impact perspective, I think this is a solid idea, too, beyond all the nuggets of wisdom you shared! :) https://greenly.earth/en-us/leaf-media/data-stories/the-carbon-cost-of-streaming